Q and A with Anita

We learn a lot about the private lives of the women portrayed in the book. Do you think Americans will be surprised to see these strong-willed women living underneath their chadors?

Iran and Iranians have become increasingly mysterious to Westerners ever since the United States severed relations with the country nearly thirty years ago. When I tell people about an ordinary activity like smoking apple-flavored tobacco in a cafe in Isfahan, I get a flurry of bewildered questions about everything from food to the status of women. In my novel, I posit that seventeenth-century women would have been quite strong in their own spheres, meaning the home, in social centers like the bathhouse, in raising children, in supervising house-related staff and purchases, and in craft-related work performed at home. I think these are quite reasonable assumptions. When it comes to Iranian women today, it would be a gross misconception to think of them as shrinking violets. Iranian women represent 60 percent of the students enrolled in universities, and in recent years, have been quite organized in fighting for their rights. One of these women, of course, is Shirin Ebadi, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2003 for her human rights work and the first Muslim woman to be so honored.

Another pervasive stereotype about Middle Eastern women is one familiar to us from the great Orientalist painters like Eugene Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jean-Leon Gerome. As much as we may admire the beauty of their paintings of, say, naked women at the bathhouse, it’s impossible not to notice that their ‘male gaze’ focuses on things like sensual dates, split pomegranates, and of course, lush female body parts. One of my key concerns in writing the novel was to portray women as they might have seen themselves. The bathhouse, for example, becomes a place that’s not about male desire, but where ordinary women go to get clean, socialize, take or give counsel, and transact business such as seeking spouses for their children. My goal was to provide a more nuanced view of pre-modern Iranian women.

How common were women rugmakers?

Very common, just as they are today. On a recent trip to Iran, my family and I stayed in a hotel in the town of Kashan and noticed that a loom had been set up in the lobby, displaying a half-finished rug. A woman came to work on it every morning, and the hotel staff told us that the rugs she made always sold before being finished because guests would fall in love with them. In small villages and among nomadic tribes, women and their daughters made all kinds of knotted goods (and still do) including rugs, saddlebags, cushions, tent coverings, and so on, which were used by the household or contributed important revenue to it when they were sold. Men and boys also learned to make rugs, and it is almost certain that highly skilled artisans who worked in the royal workshops described in my novel were men performing at the absolute pinnacle of their craft. (I’ll note in passing that I avoid the term ‘weavers’ because Iranian rugs are typically created knot by knot, as opposed to being woven through an intersection of warp and weft threads).

The heroine learns how to knot rugs from her uncle, a wealthy rug designer in the court of the legendary Shah Abbas the Great. Tell us about the impetus to this storyline.

Many people have heard about medieval rulers like Tamerlane or Genghis Khan, but I’ve been surprised by how little Shah Abbas is known in the West, given that he was one of the great monarchs of all time. Shah Abbas took control of Iran when he was only seventeen, guided the country out of a state of utter political chaos, and led it firmly for more than forty years. In addition to his talents as an administrator, Shah Abbas was an ambitious urban planner along the lines of Sheikh Mohammed of Dubai, but rather than building islands in the shape of palm trees, his projects included refashioning the city of Isfahan into the marvel that it is today. The shah had great admiration for architects, engineers, calligraphers, tilemakers and other craftspeople, and used the best minds of his court to create the “Image of the World” (the great square of Isfahan), which was a source of astonishment to foreign visitors and still attracts countless tourists. The Shah loved crafts to the extent that he was said to be expert at a number of them, including weaving cloth. To fund the state coffers, he created workshops for carpet making, since hand-loomed silk rugs were starting to become known and admired in Europe. In 1601, for example, King Sigismund III of Poland ordered Iranian rugs made with real silver thread and with his coat of arms. Hand-made carpets also started to appear in seventeenth century paintings by Rembrandt, Rubens and Velazquez, often in formal portraits of the kings and noblemen who could have afforded them.

How good were the Iranian rugs of the period?

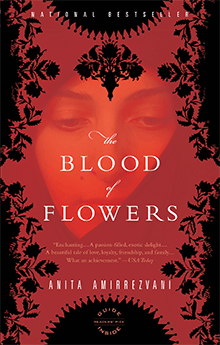

Some of the greatest carpets ever made were produced in Iran during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As an example, for the cover of my book, my publisher chose one of the two Ardabil carpets, which are thought to have been made for a shrine housing Shah Abbas’ ancestors in the north-western town of Ardabil. One of these carpets was finished in 1540; we know this precisely because the date of completion (in the Islamic calendar) was actually knotted into the rug, which was rare. The Ardabil carpets are unbelievably fine, with at least 300 knots per square inch, and so detailed that each one probably took eight men three-and-a-half years to create. When the Victoria and Albert Museum in London reopened its Islamic galleries in 2006, the curators described it as “one of the star objects” and made it a centerpiece of the permanent collection. (The other Ardabil is housed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.)

The main character of the story ends up entering into a temporary marriage called a sigheh. Can you explain what that is, and what inspired you to incorporate this unusual arrangement into the story?

Sighehs have been part of Iranian culture for hundreds of years. They allow a man and a woman to marry each other for a temporary period of time, and any children born from such unions are considered legitimate. Men pay women for this privilege, and the participants determine how long the arrangement will last. Such marriages can be made for as little as an hour or can go on forever. Understandably, public perceptions of this form of marriage have fluctuated with the times. I decided to incorporate the custom into my novel because it creates a unique set of complications for the heroine, including a Sheherazadian-like deadline as the termination date of the marriage approaches.

The main character’s name is never revealed in the book. Why?

One morning when I was looking around my living room at my Iranian rugs, embroidery, and miniature paintings, it occurred to me that none of the work was signed. As in most parts of the world, the identity of the craftsperson was considered unimportant and went unrecorded and unrecognized. When I was writing my novel, my thoughts turned to the lives of these artists, and I began to wonder where they came from, what their stories were, and whether they were still alive. My heroine could well have been one of their ancestors. By not naming her, I hoped to point out that no records exists of these craftswomen (and men) who lived, breathed, and made beautiful things that we admire so deeply. In short, my goal was to acknowledge the labor of the ‘unnamed craftsperson’ whose work has endured through the centuries. To this day, most Iranian carpets are not signed in any way.

You blend your heroine’s story with those of several traditional Persian tales. Tell us about these tales—how would you relate their significance in Persian culture to a modern American audience?

Many travelers to Iran in the pre-modern era reported with surprise that illiterate peasants could recite extremely long passages of poetry. The place of poetry cannot be overestimated in the culture; it has always been considered the highest art, and many epic poems by celebrated authors such as Rumi, Attar, and Sa’adi include retellings of traditional tales. When I was writing my book, it occurred to me that although Westerners are familiar with European tales collected by the Brothers Grimm, as well as with the Greek and Roman myths, and with A Thousand and One Nights, Iranian oral culture is little known to the general American public. There are seven tales in my novel, some of which come from sources that are about a thousand years old. I wrote the first and the last tales myself because I needed stories that reflected the emotional arc of the book.

As an Iranian-American, how do you come to terms with the tenuous relationship between the two countries?

It’s fascinating to look back at what has changed between the US and Iran in the last 30 years. In the 1970s, there were about 40,000 Americans working in Iran and relations were quite open. Ever since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, relations have been sour and the knowledge of each other at an ordinary, human level has steadily decreased. That’s one of the reasons I wrote my novel. After so many years of blackout when it comes to Iran, I thought people might be interested in learning things about it that go beyond the politics of the moment. After all, Iranian culture has been around for thousands of years, and that’s what will endure into the future. When you travel through the country, you can literally see the layers of history in monuments going back into ancient times. I wanted to give readers insight into the soul of the culture: the wedding customs, the cuisine, the life of women, the craft of rugmaking, and the uses of traditional storytelling—the things that have made Iran what it is and Iranians who they are. In doing so, I hope to get beyond the headlines and broaden the dialogue about Iran.